THE PORTRAIT PLAYERS

"Ye Gentle Spirits"

4pm Saturday 14 June 2025

St James' Church

This afternoon’s themed concert features songs inspired by the words of William Shakespeare (1564-1616) and his contemporaries. Shakespeare’s plays themselves include plenty of musical moments; in fact, several passages are marked to be sung, either by a character in the play or by a separate musician. The Tempest (c. 1610-11) is especially notable in this regard, for in addition to songs, its stage directions call for music and sound effects. The significance of music in Shakespeare plays has led many directors past and present to include music in their productions. For example, the noted actor and director Kenneth Branagh often partners with Scottish composer Patrick Doyle to create new songs for his Shakespeare films; in Much Ado about Nothing (1993), as one case in point, Doyle himself appears on screen to sing his own haunting version of ‘Sigh No More’. In other instances, Branagh enhances the role of music in films such as Love’s Labour’s Lost (2000), his valentine to the Hollywood musical. Here, he adds songs from the 1920s through the 1940s coming from classic songwriters such as George and Ira Gershwin, Cole Porter and Irving Berlin. Such musical choices keep Shakespeare’s works fresh for modern audiences. But what sort of music might people have heard when they went to the theatre during Shakespeare’s time and in the century that followed? Answering this question is exactly what prompted The Portrait Players to create their sublimely titled programme ‘Ye Gentle Spirits’.

The most popular type of solo song in Shakespeare’s England was the lute song, in which the singer’s voice would be complemented by the gentle sounds of a lute. The popularity of this genre in Shakespeare’s time cannot be overstated. More recently, the lute song’s innate sense of intimacy led the British singer-songwriter Sting to work with the Bosnian lutenist Edin Karamazov on the album Songs from the Labyrinth (2006). One song we’ll enjoy today, ‘Have you seen but a bright lily grow’, appears on Sting’s album.

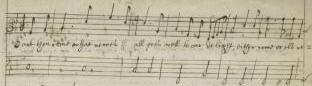

Another feature of music developing during Shakespeare’s time was the idea of basso continuo, which featured two instruments. One, usually a cello or a viola da gamba (the latter a bowed string instruments with frets, like a lute or guitar), would play the bass line, the lowest-sounding part. The other would provide harmonic texture and could be some sort of keyboard (such as a harpsichord or organ) or a plucked string instrument (such as a lute or guitar). The norm was for only the melody and the bass line to be notated, sometimes with numbers under the bass line to indicate how the harmony should work. It was up to the harmony player to ‘realise’ or create their part to fit with the lower bass line and the upper vocal line. We’ll hear plenty of this characteristic texture—a voice, a harmony instrument and a bass instrument—in this afternoon’s historically informed performance.

Musical notation featuring a sung line and a bass line, leaving the harmony to be ‘realised’. New York Public Library.

Of the composers included in today’s concert, a special pride of place must go to Robert Johnson (c. 1583-1633). Johnson is the only composer we can identify by name whose songs were performed during the first performances of Shakespeare’s plays. The composer worked closely with the King’s Men, the theatrical company that produced plays not only by Shakespeare but also by Ben Jonson, Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher. This afternoon, we’ll hear Johnson’s settings of texts from all four playwrights. Johnson’s music serves to amplify the overall moods of the respective lyrics. For example, the joyfulness of ‘Hark! Hark! the lark!’ is further enhanced through vocal flutters and flourishes along with a rising melodic line that suggests a bird taking flight. (The latter technique is known as ‘text painting’, where the music does what the words say.) The playfulness of ‘Come hither you that love’ is contrasted with a pervasive sense of longing in ‘Have you seen but a bright lily grow?’ And in ‘Woods, rocks and mountains’, mournful qualities resound through multiple descending lines. Throughout his career, Johnson also held court positions as a lutenist, and it is very likely that some of his theatrical music would have been heard at court.

The brothers Henry (1596-1662) and William (1602-1645) Lawes both wrote songs for the theatre. Henry was a gifted singer who sang with the Chapel Royal during the reign of Charles I. A committed royalist, his anthem Zadok the Priest was performed at the coronation of Charles II in 1661. Henry’s younger brother William was a virtuoso on the viol and a highly gifted composer, especially of viol music. William spent his entire adult life in the employ of Charles I. He joined the royalist army during the British civil wars and died tragically after a roundhead shot him at the Battle of Rowton Heath on 24 September 1645. William’s death had a profound effect on Henry, whose 1648 publication Choice Psalms, a collection of three-part psalm settings by himself and William, was conceived as a memorial to his deceased brother.

Two other composers featured today were early holders of the post Master of the King’s Musick, the musical equivalent of Poet Laureate. Nicholas Lanier (1588-1666) was the first to be honoured with the title in 1626. Lanier was not just a composer but also a talented singer, lutenist, viola da gamba player, set designer and painter. John Eccles (1668-1735) became Master of the King’s Musick in 1700 and is the only person to have held the post under four monarchs: William III, Anne, George I and George II. Eccles was especially known for his songs and music for the theatre. Lanier and Eccles were both captivated by the new Italian style of recitative, in which a musically enhanced declamation of the text leads to tremendous and often achingly beautiful dramatic effects. We’ll hear this powerful means of musical storytelling in Lanier’s extensive scena ‘Hero and Leander’ (c. 1628), which Charles I often commanded Lanier to sing for his own personal pleasure. It also infuses Eccles’s emotionally charged setting of ‘I burn’ from Thomas d’Urfey’s The Comic History of Don Quixote (1694), a dramatisation of Miguel de Cervantes’s novel Don Quixote (published in two parts, 1605, 1615).

Eccles was not the only composer to contribute music to d’Urfey’s three-part, seven-hour stage adaptation of Don Quixote. Another was Henry Purcell (1659-1695), one of the most celebrated composers of the English Baroque. Purcell composed a great deal of instrumental works and sacred music, though it was his music for the theatre that made him famous. The majority of Purcell’s musical works for the stage are often called ‘semi-operas’, a hybrid of spoken-word plays, sung-through operas and pieces that exist purely for entertainment. The pure entertainments, often called masques, were usually allegorical in nature and sometimes featured the evening’s hosts as performers. Such is the case with The Fairie Queen (1692), an anonymous adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Purcell didn’t actually set to music any of Shakespeare’s original texts as they appear in the so-called ‘Restoration spectacular’ but rather created music for its allegorical entertainments. This afternoon we’ll hear some of the songs Purcell wrote for The Fairie Queen as well as one of his songs for The Comic History of Don Quixote, ‘From rosy bowers’. This brilliant tour-de-force features a chambermaid who pretends to be mad as part of a plot against Don Quixote. Its virtuoso vocally dramatic depictions of love, happiness, melancholy, passion and mad frenzy make it a fitting finale to this afternoon’s programme.

The Portrait Players is a UK-based trio founded in January 2023. The ensemble has quickly established itself as a significant presence in the early music scene and has become especially known for its innovative programming and consummate artistry. With a focus on music of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, its members are Claire Ward (soprano), Kristiina Watt (theorbo and lute) and Miriam Nohl (Baroque cello and viola da gamba). The trio’s members have performed with many of Europe's leading early music ensembles, including The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, The Academy of Ancient Music, La Nuova Musica, The English Concert and The Monteverdi Choir.

-Notes by William Everett